Search Strategies

On this page

- Getting started

- Some tips before you begin

- Diverse perspectives

- Searching Yale Libraries catalogs

- Database search strategies

- Citation tracing as a search strategy

- Before you go…

Getting started

Given the great variety of discovery tools for primary sources, it is probably unsurprising that there is no single, one-size-fits all strategy for searching for primary sources. The search strategies you use should be tailored to your research topic and to particular discovery tools.

Some tips before you begin

Undertaking research with primary sources can be a daunting task. Having a plan before you begin will help you stay organized as you research your topic. A few tips to keep in mind as you begin your research:

- Write down your research question(s) before you begin.

- Write down some search terms to get you started and keep track of the keywords you search. If you think of others as you’re searching, add them to the list.

- Decide on a method of keeping your results and notes organized, either by using a citation manager or some other process. There is a LibGuide on citation management here.

- Most importantly, be patient. Research is an ongoing process, and it takes time.

Keep an open mind as you undertake your research. You may find new terms or keywords to search that you had not thought of. Some of the tips below will help you in your work locating primary sources.

Searching in catalogs and databases can be similar to searching in Google, but there are important differences in how you phrase searches. You can search by a simply stated topic, like “Jim Crow laws.” You can’t search by a sentence or phrase as you can in Google, like “Important court cases about the Jim Crow laws.”

Diverse perspectives

In your search for primary sources you may question why some material is harder to find than other material. It is important to understand that archival and historical collections are social constructions that represent the context of their creation. Social, political, and economic forces shape the creation of primary and secondary sources at any particular historical moment. Therefore minority voices and the lives of the less powerful are not always well represented in library and archival collections.

Consider the who, what, where, when, and how of collection creation. You may find that the perspectives you are seeking are difficult to uncover. Be creative in your searching, and you may discover those perspectives in unexpected primary sources found in unusual locations. Consult librarians, archivists, historians, and subject specialists for additional tips on hunting down hard-to-find primary sources.

Searching Yale Libraries catalogs

A lot of researchers start with Orbis or Quicksearch, since those catalogs also search other catalogs and databases at Yale, or have copies of records that are in other catalogs or databases. Orbis and Quicksearch have differing search capabilities, so it can be helpful to perform your search in both catalogs. To help you get started:

- Morris (the Law Library catalog) can be searched through Quicksearch, but not through Orbis.

- Archives at Yale is not searchable through Orbis or Quicksearch. However, many of the collections in Archives at Yale also have collection-level records in Orbis and Quicksearch, with links to request through that system.

- Aviary is not searchable through Orbis or Quicksearch. However, many of the materials in Aviary also have records in Orbis and Quicksearch, with links to request through that system. Links to Aviary also appear in some collections in Archives at Yale.

How to perform a basic Boolean search

The type of search researchers often perform are basic keyword searches, with one word or a few words. This can cast a wide net, but the flip side is that it will often bring back irrelevant items. This can also be complicated by how the system searches the words you put in. Some systems, like Orbis, will automatically look for matches that have all the words present. Others, like Aviary, will automatically look for matches that have at least one or more of the words present. In cases where you use more than one word, using Booleans will be more effective.

A Boolean search uses the operators AND, NOT, and OR to filter results. Understanding how to use these operators can help you quickly narrow a search without having to sift through pages and pages of results for a single keyword search. If you are using a phrase as a keyword, you must enclose it in quotation marks, otherwise the search will treat each word as an individual keyword to search. Boolean operators function as follows:

AND: Searches for both of these keywords in the same result

- Example: Women AND Victorian fiction

OR: Searches for one or the other of these keywords, but not both in the same result

- Example: Medieval OR “Middle Ages”

NOT: Searches for this keyword but not that keyword

- Example: Alabama NOT Mississippi

In systems like Orbis, MORRIS, and Aviary, you can directly enter the Boolean operators into a keyword search bar as written above. Quicksearch uses a relevancy algorithm in retrieving results, and you may use the Boolean operators or symbols + and - to include or exclude terms. It can also be useful to enclose phrases in quotation marks. For more extensive searches, start with the advanced search page . To learn more about advanced search pages, take a look at the section below.

Wildcards, truncation, and other limiters

In combination with the basic search strategies above, you can also use the following strategies to narrow your search.

Many catalogs and databases use characters, called wildcards, to help broaden or focus your search, and still keep it relevant. Each system may use a different wildcard system. A common example is to use a character in keywords for variant endings or internal spelling.

- Example: In Orbis, child? finds child, children, childhood, etc.

- Example: In Aviary, *stadt will match terms that end with “stadt” (Litzmannstadt, Theresienstadt, etc.)

- Example: In HathiTrust, ? will stand in for a single character (wom?n will find woman and women) and * will stand in for several characters (optim* will find optimal, optimize or optimum)

- Example: In Quicksearch play will also retrieve plays and playing (common singular and plural forms, and some related forms, in English). There is currently no wildcard or truncation symbol.

To learn about the different wildcards and truncations available in each catalog or database, look at the help documentation for each system.

Many catalogs and databases have limits, filters, and facets which you can use to narrow down searches, such as date ranges, languages, format, or library location. Be careful about filtering too much though, especially if you’re not completely sure what materials you are looking for- you might accidentally leave out useful materials.

As you focus your research, you can combine these operators into a more advanced string.

- Example: artist AND wom?n AND (California OR Mexico)

Material search

The library catalog is a great place to begin searching for primary sources. If you are looking for primary sources in electronic catalogs like Orbis and Quicksearch, certain keywords will help you. Some words that are particularly useful include:

- Archives

- Correspondence

- Diaries

- Documents

- Interviews

- Manuscripts

- Microfilm

- Oral history / oral histories / oral narratives

- Pamphlets

- Photographs

- Personal narratives

- Sources

- Speeches

Many catalogs and databases will have options in their search interface and/or their results interface for you to pick out what formats you would like to work with. For example, the results page of the Yale University Art Gallery search will include filters that let you narrow down to not only the type of item something is, but the material the item is made of!

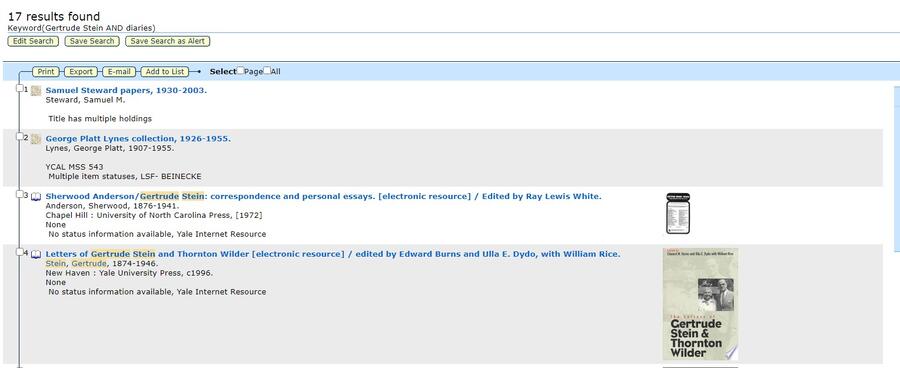

You can combine these terms with other keywords using Boolean operator terms to narrow down your results.

- Example: Gertrude Stein AND diaries

When searching by format, keep in mind how those formats would be used and how it may impact your search. For example, the creator of a piece of correspondence will likely not have a copy of it - it would be with the recipient and you’ll need to consider their collection too.

You can also use the advanced search features in Orbis and Quicksearch to help you quickly narrow your search within the collections.

Subject headings search

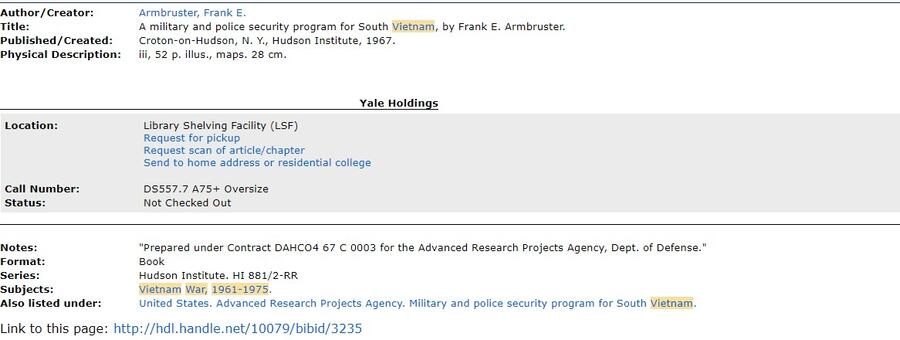

Subject heading searches often return more comprehensive results than keyword searches. The Library of Congress creates subject headings that most libraries borrow, but they might not obviously come to mind. One way to find out the subject heading for a particular topic is to look for a trusted source in the library catalog and examine the record to find the subject headings.

For example, the subject term for the Vietnam War includes the dates: Vietnam War, 1961-1975. To find relevant subject headings, a researcher should run a keyword search to find a trusted source in the catalog, then look at the subject headings listed at the bottom of the record.

- Example: Vietnam War, 1961-1975

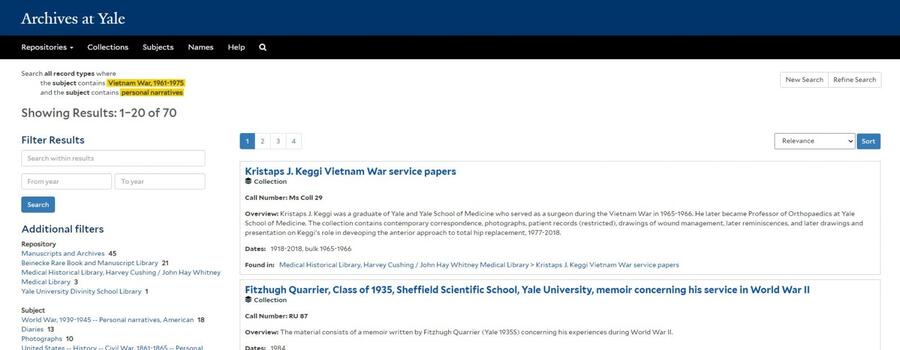

A search that combines primary source keywords with subject headings will likely bring back relevant material. For example one could search Vietnam War, 1961-1975 AND personal narratives to find memoirs or firsthand accounts of soldiers who fought in the war.

- Example: Vietnam War, 1961-1975 AND personal narratives

Advanced searches

Combining different types of searches using Boolean methods can be made in the simple search bar of most systems, but catalogs and databases have advanced search features. Not only do they simplify writing and structuring searchers with multiple parts, they allow researchers to be quite nuanced in their searches.

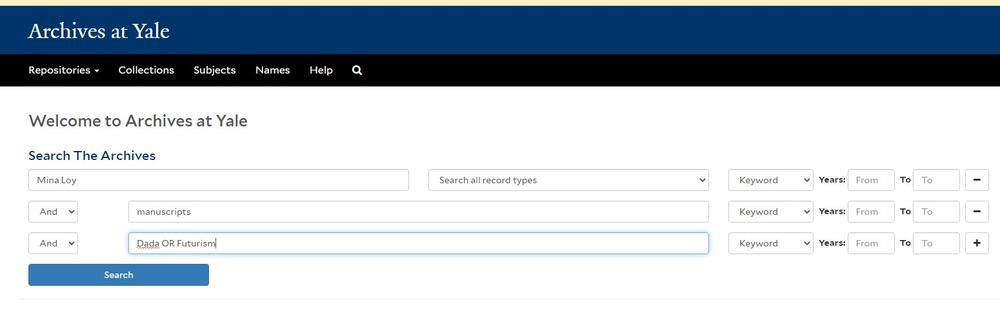

Advanced search pages use the same Boolean logic of simple search pages, but give researchers multiple search bars and options for selecting the wanted operator. Instead of putting in a long string like “Mina LOY AND manuscripts AND (Dada OR Futurism),” you can write each of those terms in their own search bars and select the Boolean operators you want to use from dropdown menus. You can also still put in Boolean operators within those fields too. This can help simplify structuring searches with nesting

- Example

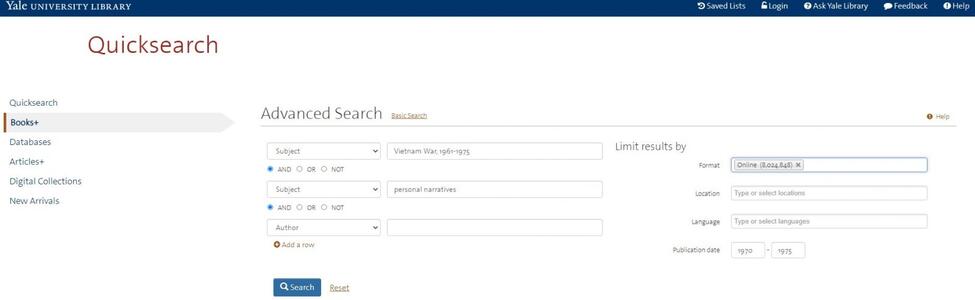

Another advantage of advanced search pages is the ability to limit individual search terms to specific parts of records, like titles or subject headings, as well as over all possible fields. This can be helpful in cases where you are making sure you are finding material by the right creator, or if you are trying to use multiple topical terms to broaden your search. Also important is that formats, languages, and dates are their own criteria in most advanced searches. You don’t need to put in dates or formats in the search bars. Rather, you can select them from specially designated dropdowns. Therefore, a user can search Vietnam War, 1961-1975 AND personal narratives, and limit results to those written from 1970-1975 and records in electronic form.

- Example

Database search strategies

You can use the same basic search strategies you use in catalog searches to search within databases.

Additionally, in many primary source databases, you will have the opportunity to search the full text of documents. Think about the language that would have been used during that time period and in that cultural context, and search for relevant words, names, or phrases.

Citation tracing as a search strategy

One good way to discover primary sources relevant to your research question or topic is to check the citations and bibliographies in books, articles, and dissertations related to your project. You can search for all of these sources in Quicksearch. Whether citations appear as endnotes or footnotes, they can be very helpful in leading you to primary sources found in archives, as publications, on microfilm, and online.

Bibliographies in books and dissertations often separate out lists of the primary or archival sources consulted, and if you are lucky, you might find a bibliographic essay at the end of a book or dissertation that not only identifies primary source materials but also describes the type and quality of information they contain.

Don’t be discouraged if you do not immediately find relevant sources and materials, or if you are having trouble narrowing results. Think about how you are searching and the keywords you are using. Use filters and facets to narrow down searches. Remember, research takes time and patience!

If you have questions or need help with any aspect of searching collections, librarians are here to help.